___________________________________

Industrial Liaison Group:

Tel: +44 (0) 1235 778797

E-mail: [email protected]

Diffraction is a natural phenomenon and an important tool that helps scientists unravel the atomic structure of our world. You will encounter diffraction every day; in the murmur of background noise or the levels of heat or light in a room – all of these are related to diffraction. Think of waves on the ocean; they behave in the same way as light and sound. When water waves hit an object like a rock or a boat, their trajectory is changed and they disperse in a different pattern. The same is true of light and sound waves.

It is possible to have a covert chat in the workplace because the sound from your conversation bounces off walls and is spread out as it hits surrounding objects. This causes the waves to become distorted so that they reach others as a murmur of blurred sound. It’s not just sound; light and heat are also affected by diffraction.

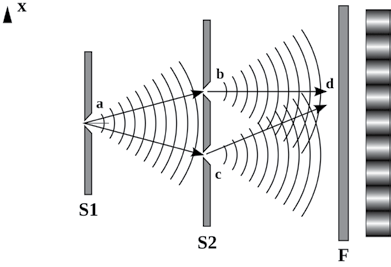

Wave diffraction was first observed in the 17th century, but it wasn’t until 1803, when Thomas Young performed an experiment to observe waves diffracting through two slits, that the phenomenon began to be more fully understood.

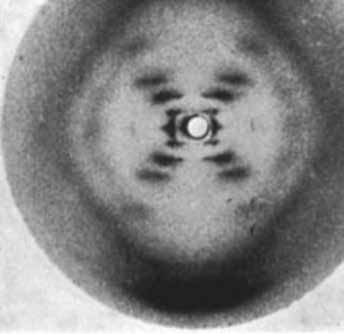

In 1912, Max von Laue and colleagues at the University of Munich, Germany came up with the idea to send a beam of X-rays through a copper sulfate crystal and record the results on photographic plates. He persuaded his colleagues Walter Friedrich and Paul Knipping – both of whom had more practical experience with X-rays than von Laue himself – to perform the experiment, the results of which showed diffraction spots surrounding the central spot of the primary beam.

The discovery came 17 years after Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen had first demonstrated the existence of X-rays and their nature was still undetermined. Physicists suspected that X-rays were a form of electromagnetic radiation, but had been unable to obtain solid evidence for their diffraction. Von Laue's experiment presented evidence for the wave nature of X-rays and the space lattice of crystals at the same time as the diffraction spots were caused by X-rays impinging on a regular array of scatterers, in this case, the repeating arrangement of atoms within the crystal. The scatterers produced a regular array of spherical waves which gave the bright spots on the photographic plate.

Within a year of this discovery, in 1912, William Henry Bragg and son Lawrence had exploited the

phenomenon to solve the first crystal structure and create a mathematical formula, Bragg’s Law, which showed how to work out the atomic structure of a sample based on the diffraction pattern it produced when exposed to X-rays.

The discoveries of von Laue and Bragg gave birth to two new sciences, X-ray crystallography and X-ray spectroscopy, and two Nobel Prizes: Max von Laue “for his discovery of the diffraction of X-rays by crystals” in 1914 and to Bragg and his father, Sir William Henry Bragg, “for their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays” in 1915.

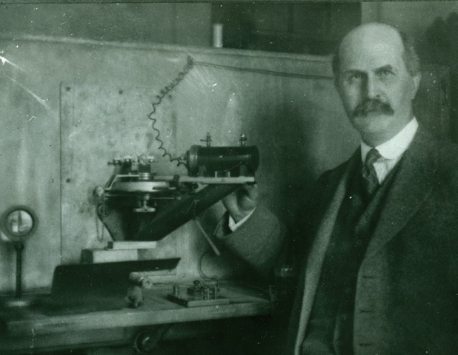

William Henry Bragg with the first spectrometer.

Courtesy of The Royal Institution

If you shine a bright light at an object, it produces a diffraction pattern as it leaves the sample. This is because the light bounces off each atom inside the object, creating a unique arrangement of light and dark spots. This pattern can then be used to identify the atomic structure of the object itself.

Diffraction patterns provide the atomic structure of molecules such as powders, small molecules or larger ordered molecules like protein crystals. It can be used to measure strains in materials under load, by monitoring changes in the spacing of atomic planes.

Some samples can be tricky to study using diffraction. That’s why scientists use a technique called crystallography to freeze their samples into ice-like crystals. If it’s crystallised first, then almost anything – from virus structures to ancient fossils – can be studied using diffraction.

The main diffraction techniques employed at Diamond are:

Single crystal diffraction is the most widely used technique for obtaining full three-dimensional structural information of solid-state crystalline materials. This allows characterisation of, for example, molecular packing, guests in a framework structure, the nature of intra- and intermolecular interactions, molecular conformation and static and dynamic disorder. Environmental cells can be used to probe materials under a range of non-ambient conditions.

Single crystal diffraction is the most widely used technique for obtaining full three-dimensional structural information of solid-state crystalline materials. This allows characterisation of, for example, molecular packing, guests in a framework structure, the nature of intra- and intermolecular interactions, molecular conformation and static and dynamic disorder. Environmental cells can be used to probe materials under a range of non-ambient conditions.

The ability of the synchrotron to obtain time-resolved data allows the investigation of short-lived excited states, rapid structural changes in solid-state reactions and order/disorder phenomena that can be observed as they occur. Because the wavelength of the X-rays is tunable, it is also possible to examine complex materials using anomalous dispersion.

Useful for

Applications of this technique range from detailed analyses of new catalytic and 'smart' electronic materials to the design of new pharmaceutical products and as the starting point for computational studies and molecular modelling. Technological areas studied include catalysis, energy storage, magnetic recording, structural biology and pharmaceuticals.

Applications of this technique range from detailed analyses of new catalytic and 'smart' electronic materials to the design of new pharmaceutical products and as the starting point for computational studies and molecular modelling. Technological areas studied include catalysis, energy storage, magnetic recording, structural biology and pharmaceuticals.

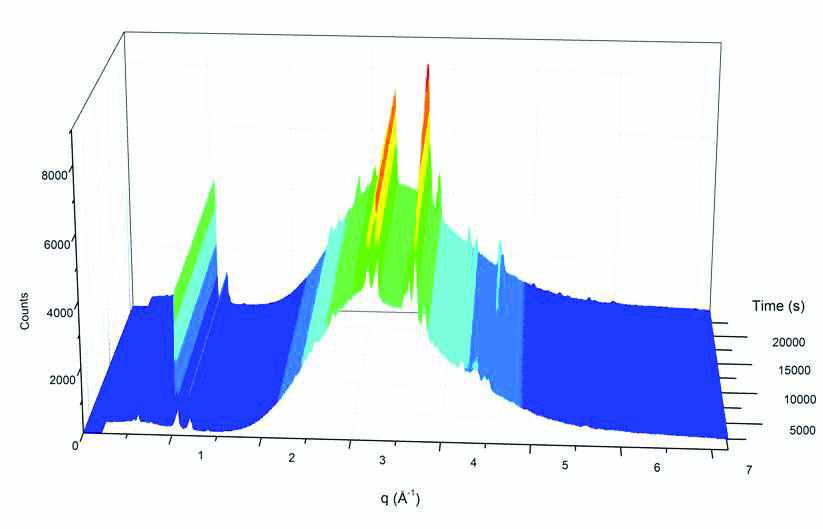

Powder diffraction is used to examine small, weakly interacting crystals in random orientations. Many materials exist as powders or in polycrystalline form, including ceramics, metals, allooys, superconductor oxides, pharmaceuticals, geochemicals, zeolites and related porous solids, all of which can be studied with powder diffraction.

Powder diffraction is used to examine small, weakly interacting crystals in random orientations. Many materials exist as powders or in polycrystalline form, including ceramics, metals, allooys, superconductor oxides, pharmaceuticals, geochemicals, zeolites and related porous solids, all of which can be studied with powder diffraction.

High quality, high resolution powder patterns can be recorded with short scan times via multi-element analyser stages while fast, wide-angle position sensitive detectors allow the rapid collection of powder patterns in time-resolved studies in non-ambient conditions.

The high resolution opens the possibility of novel studies of phase transitions in large macromolecules as a function of temperature, leading to improved methods for the preparation of large single crystals. The high intensity X-rays can probe more deeply into the sample than laboratory techniques, and the use of resonant diffraction allows complex structures with low "normal" electron contrasts to be studied.

Useful for

Refinement of the structures of organic molecular pharmaceutical solids; determination of the effect of competing effects in highly correlated oxides and chalcogenides; the study of structural changes in polymer lithium ion conductors; the structure of porous materials and of nanoscale systems formed by inclusion within the pores and the time dependence of the intersite cation ordering in mineral phases. Technological areas studied with this technique include catalysis, energy storage, radioactive waste treatment, magnetic recording, structural biology and pharmaceuticals.

I11 - High Resolution Powder Diffraction

I12 - JEEP

I15 - Extreme Conditions

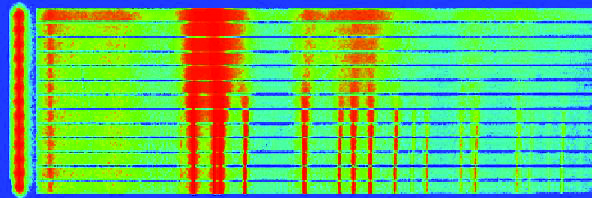

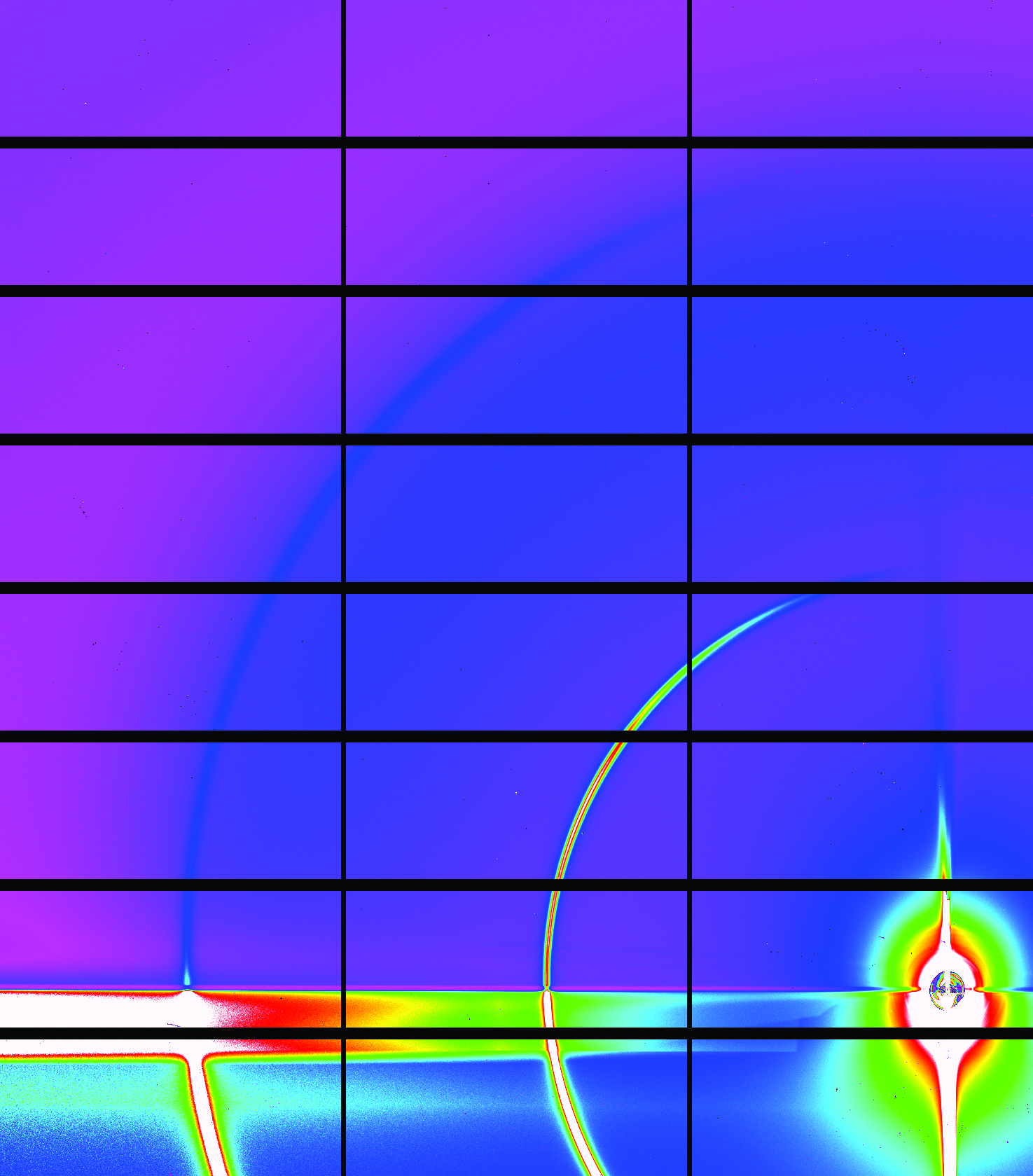

Instead of using X-rays of single energy, which is like using light of a single wavelength or colour, energy-dispersive diffraction uses a multi-wavelength "white beam" of X-rays. This polychromatic white beam can only be produced at a synchrotron and is not possible using laboratory X-ray sources. The white beam is diffracted by the sample, producing a spectrum with characteristic intensity peaks at specific photon energies. The position of these peaks provides information about the crystal structure of the sample.

Instead of using X-rays of single energy, which is like using light of a single wavelength or colour, energy-dispersive diffraction uses a multi-wavelength "white beam" of X-rays. This polychromatic white beam can only be produced at a synchrotron and is not possible using laboratory X-ray sources. The white beam is diffracted by the sample, producing a spectrum with characteristic intensity peaks at specific photon energies. The position of these peaks provides information about the crystal structure of the sample.

Shifts in peak position are used to measure internal strains. By scanning the sample through the beam, a 2D or 3D map of strains in the sample can be produced.

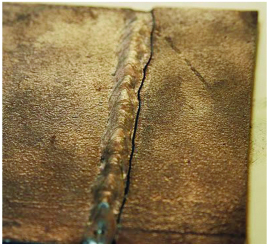

The high energy of X-rays from a synchrotron allows the technique to be used on thick samples, such as real engineering components. The high intensity reduces data collection times, so larger samples can be scanned to map internal strains. The great strength of this technique is that it allows for non-destructive testing of materials.

Useful for

Strain-scanning of engineering components, for example measuring residual strains in a weld that could cause cracking in service. The high energy and high intensity X-rays can be used to "see" inside chemical processing equipment or high pressure cells. This opens up the possibility of studying chemical reactions and processes in bulk materials under realistic processing conditions.

Strain-scanning of engineering components, for example measuring residual strains in a weld that could cause cracking in service. The high energy and high intensity X-rays can be used to "see" inside chemical processing equipment or high pressure cells. This opens up the possibility of studying chemical reactions and processes in bulk materials under realistic processing conditions.

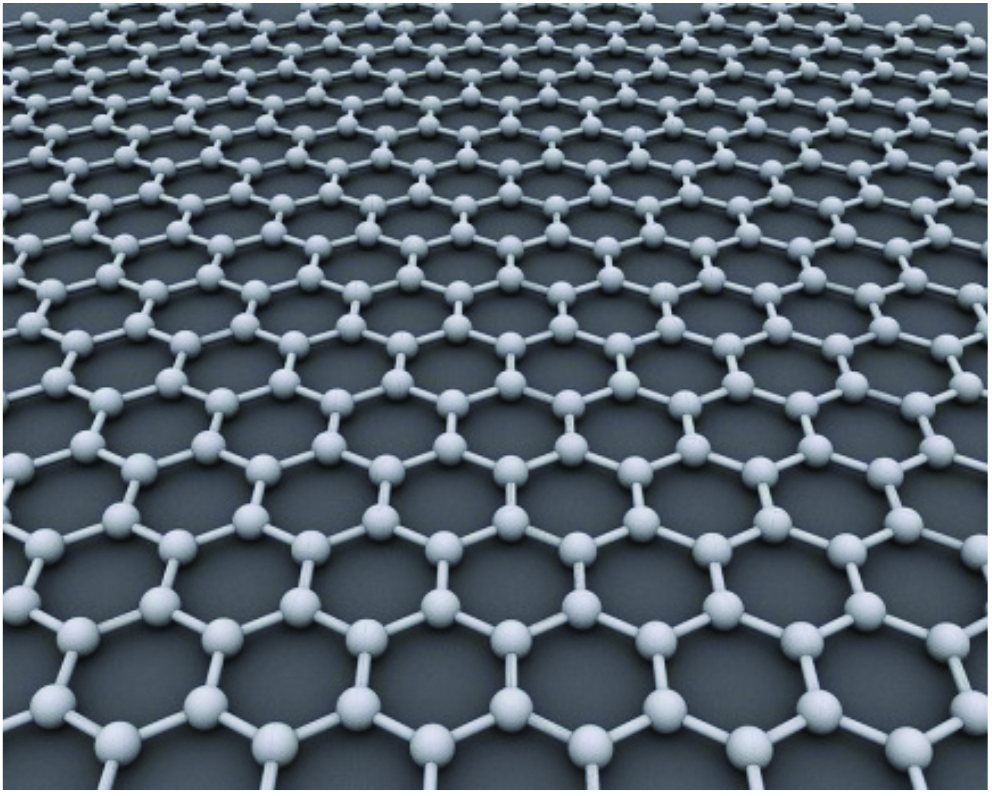

Surfaces and interfaces determine many of the properties of materials, including electronic, magnetic and chemical behaviour. Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction (GIXD) is an ideal tool for determining the morphology of novel materials in realistic operating conditions.

Surfaces and interfaces determine many of the properties of materials, including electronic, magnetic and chemical behaviour. Grazing Incidence X-ray Diffraction (GIXD) is an ideal tool for determining the morphology of novel materials in realistic operating conditions.

The penetration of synchrotron X-rays through matter and the provision of environmental chambers means that a wide range of systems and environments can be studied, including; gas-solid, liquid-solid and solid-solid interfaces. Combining synchrotron techniques including X-ray diffraction in a grazing incidence geometry, measurement of diffuse scattering, grazing incidence small angle x-ray scattering (GISAXS) and X-ray reflectivity make it possible to accurately establish the structure of a material, which can be correlated with the function of the interface in realistic operating conditions.

Useful for

Surface and interface diffraction is an ideal tool for examining the atomic structure of materials, and establishing links to their behaviour. The measurement of strain at interfaces, for example, can inform on whether a component will be able to function in realistic operating conditions. The use of interchangeable environmental stages (ultrahigh vacuum, electrochemical and high gas pressure) means that a great range of technically demanding systems can be investigated, including complex alloy semiconductor and oxide surfaces, quasi crystals, polymers and biological films.

Surface and interface diffraction is an ideal tool for examining the atomic structure of materials, and establishing links to their behaviour. The measurement of strain at interfaces, for example, can inform on whether a component will be able to function in realistic operating conditions. The use of interchangeable environmental stages (ultrahigh vacuum, electrochemical and high gas pressure) means that a great range of technically demanding systems can be investigated, including complex alloy semiconductor and oxide surfaces, quasi crystals, polymers and biological films.

I07 - Surface and Interface Diffraction

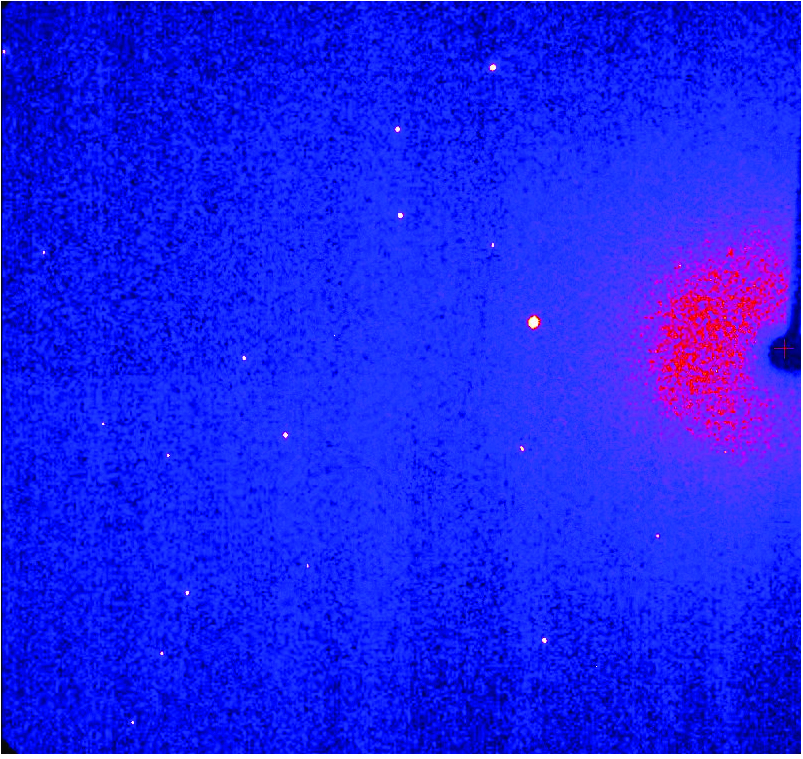

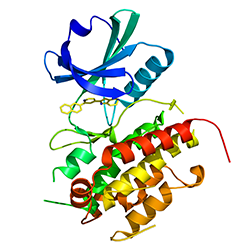

Macromolecular Crystallography (MX, also referred to as Protein Crystallography or PX) is the most powerful method for determining the atomic three dimensional structures of large biological molecules. It is a vital tool for linking structure with function, for rational drug design, for investigating protein folding and for relating other structural information, such as evolutionary relationships, from biological molecules.

Macromolecular Crystallography (MX, also referred to as Protein Crystallography or PX) is the most powerful method for determining the atomic three dimensional structures of large biological molecules. It is a vital tool for linking structure with function, for rational drug design, for investigating protein folding and for relating other structural information, such as evolutionary relationships, from biological molecules.

The Diamond MX beamlines allow structure determination by molecular replacement, where the structure of a related molecule is already known, by standard isomorphism replacement with heavy atoms and by Single wavelength Anomalous Dispersion (SAD) or Multiwavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD) measurements, in which the wavelength of the X-rays is tuned to be near or at the natural absorption wavelength of selected atoms in the macromolecule. This enables the detection of small differences in the diffraction pattern for reflections that are related as Friedel pairs and these differences allow phase determination to determine the structure through crystallographic methods.

Macromolecules tend to form small, imperfect and weakly diffracting crystals. The high brightness of synchrotron X-rays makes the collection of precise measurements possible. Automated remote sample handling systems allow high throughput for testing samples.

Useful for

Rational drug design, enzyme mechanisms, supramolecular structure, molecular recognition, nucleic acids, structural genomics, high throughput crystallography.

Complementary techniques are Circular Dichroism, Non-crystalline diffraction (SAXS), EXAFS & Imaging

Would you like to know more about diffraction and how you can apply it to your research? Do you perhaps have a structural problem that you are unable to solve in your lab or a material you wish to find out more about? Then please get in touch with the Industrial Liaison Team at Diamond.

The Industrial Liaison team at Diamond is a group of professional, experienced scientists with a diverse range of expertise, dedicated to helping scientists and researchers from industry access the facilities at Diamond.

We’re all specialists in different techniques and have a diverse range of backgrounds so we’re able to provide a multi-disciplinary approach to solving your research problems.

We offer services ranging from full service; a bespoke experimental design, data collection, data analysis and reporting service through to providing facilities for you to conduct your own experiments. We’re always happy to discuss any enquiries or talk about ways in which access to Diamond’s facilities may be beneficial to your business so please do give us a call on 01235 778797 or send us an e-mail. You can keep in touch with the latest development by following us on Twitter @DiamondILO or LinkedIn

Diamond Light Source is the UK's national synchrotron science facility, located at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire.

Copyright © 2022 Diamond Light Source

Diamond Light Source Ltd

Diamond House

Harwell Science & Innovation Campus

Didcot

Oxfordshire

OX11 0DE

Diamond Light Source® and the Diamond logo are registered trademarks of Diamond Light Source Ltd

Registered in England and Wales at Diamond House, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0DE, United Kingdom. Company number: 4375679. VAT number: 287 461 957. Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number: GB287461957003.