Scientists at the University of Oxford and Diamond Light Source have described a new chemical catalyst for producing methanol, a promising future biofuel. By reducing the energy needed to convert biomass to methanol, the new catalyst offers a more sustainable way to make the useful chemical and fuel.

At present, methanol is used primarily in industrial chemistry, including the manufacture of plastics and synthetic fibres, and as a fuel in fuel cells. It is manufactured from natural gas, a fossil fuel. But some biotech companies are now in the demonstration phase of synthesising methanol from biomass waste such as agricultural residues and wood chips.

The current method of producing methanol from biomass is, however, hugely energy-intensive. The tough cellulose in biomass requires high pressure and searing temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius to be broken down into carbon monoxide and hydrogen called syngas. These basic molecules are then reassembled to make methanol. Creating methanol directly from biomass molecules would require much less energy if the syngas intermediate could be avoided.

A new catalyst offers the first feasible way of doing just that. Catalysts already exist to convert cellulose into ethylene glycol, the chemical in antifreeze. Now, the palladium-iron catalyst developed by Edman Tsang and colleagues at the University of Oxford bridges the second half of the gap, transforming that ethylene glycol into methanol. The researchers report in the 11 September 2012 issue of

Nature Communications that the catalyst has high selectivity, meaning few chemical by-products and more energy-efficient conversion.

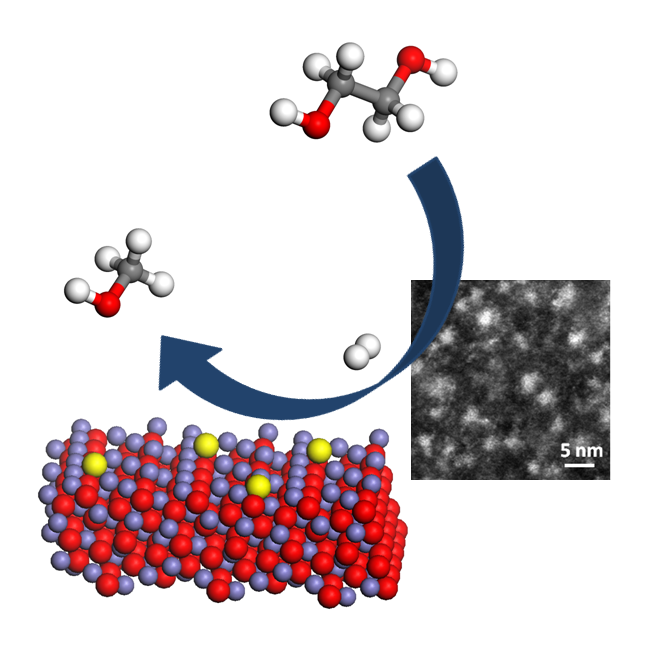

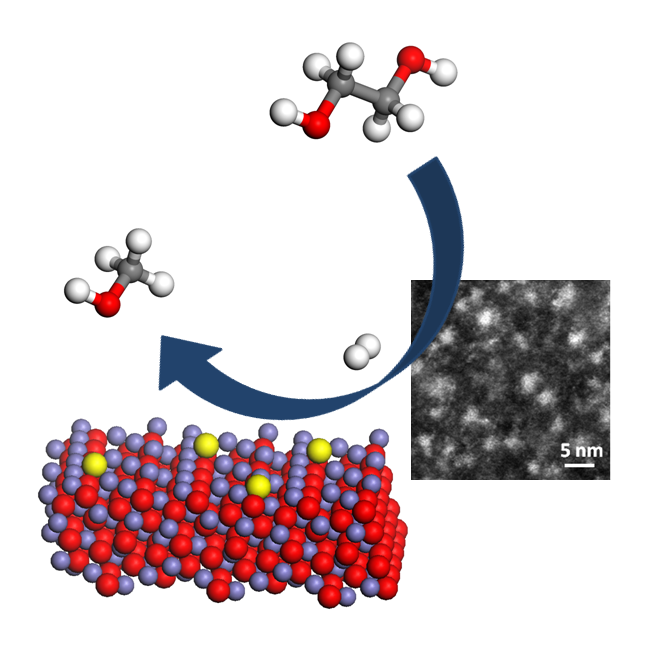

Image: Highly Dispersed Palladium-Iron Clusters for Selective Hydrogenolysis of Ethylene Glycol (Biomass-derived Chemical) to Methanol.

The catalyst consists of an iron oxide base – or more colloquially, rusty iron – coated with palladium. When this catalyst was submerged in ethylene glycol the researchers observed 80% selectivity, meaning that four-fifths of the molecules produced were useable alcohols (methanol and ethanol). With further tweaking, the team hopes to increase that output to 100%.

It remained a mystery, however, precisely how the catalyst was performing its feat. Was the palladium itself doing the conversion, or was the iron somehow coming out of the iron oxide and binding with palladium? For that investigation the researchers turned to the Diamond Synchrotron.

“The technique we used can only be undertaken on a synchrotron,” explains Andrew Dent, principal beamline scientist on Diamond’s beamline B18, where the analysis was carried out. Dent and colleagues at Diamond used X-ray absorption spectroscopy, which consists of firing precisely tuned X-rays at a sample to excite an electron from one type of atom – in this case, palladium. The electron sets up a standing wave with neighbouring atoms, resulting in a pattern of interference that provides information about the number, kind and distances of neighbouring atoms.

“The strength of the technique is that it does not require a crystalline sample,” Andrew continues, “but can be used as in this case to study small catalysis particles supported on a substrate. The experiment was carried out using Diamond’s Rapid Access procedure which allows small amounts of time to be given for an especially urgent measurement.”

The researchers found that the reaction with ethylene glycol had induced small clusters of palladium and iron to form on the catalyst surface, and that it was this chemical combination that worked the trick. Knowing this will allow the Oxford researchers to further tweak their catalyst to improve its efficiency and specificity.

“What we demonstrate here is the first example of a route to make bio-methanol, converting biological molecules to make methanol,” explains lead author Edman Tsang. “That can then be blended into petrochemicals, and can be used for energy or can be used to make chemicals. Our contribution here is, we can diversify all of those processes.”

A non-syn-gas catalytic route to methanol production

Cheng-Tar Wu, Kai Man Kerry Yu, Fenglin Liao, Neil Young, Peter Nellist, Andrew Dent, Anna Kroner & Shik Chi Edman Tsang

Nature Communications 3, Article number: 1050 doi:10.1038/ncomms2053

Received 22 March 2012, Accepted 06 August 2012, Published 11 September 2012

The current method of producing methanol from biomass is, however, hugely energy-intensive. The tough cellulose in biomass requires high pressure and searing temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius to be broken down into carbon monoxide and hydrogen called syngas. These basic molecules are then reassembled to make methanol. Creating methanol directly from biomass molecules would require much less energy if the syngas intermediate could be avoided.

The current method of producing methanol from biomass is, however, hugely energy-intensive. The tough cellulose in biomass requires high pressure and searing temperatures of 800 degrees Celsius to be broken down into carbon monoxide and hydrogen called syngas. These basic molecules are then reassembled to make methanol. Creating methanol directly from biomass molecules would require much less energy if the syngas intermediate could be avoided.