Globally, more than 70 million people were struggling with a chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection in 2015. Although effective drugs are available to treat chronic infections, only 13% of cases received curative treatment. The fact that only 20% have been diagnosed is of even greater concern. Although a minority of newly-infected individuals (10–40%) manage to overcome the disease, most develop a chronic infection. Most acute cases of HCV are asymptomatic, leading to undetected virus transmission. Left untreated chronic HCV can lead to serious liver damage and an increased risk of liver cancer. As curative therapies alone cannot eliminate the virus, a vaccine is required. However, because HCV is very diverse and evolves rapidly to evade the immune system, developing an effective vaccine is challenging. In work recently published in npj Vaccines, scientists from the MRC-University of Glasgow Centre for Virus Research, the University of St. Andrews and Imperial College London describe an alternative strategy that uses a structural mimic to encourage the immune system to make antibodies that can recognise multiple strains of the virus i.e. broadly-neutralising antibodies (bNAbs) against HCV.

With its high genetic diversity and an envelope of ever-changing glycoproteins, HCV is challenging for the human immune system to detect and counteract. The minority of cases in which the virus is successfully cleared from the body show a broad, strong T-cell response and neutralising antibodies during the early phase of infection. Individuals who have previously cleared an HCV infection have an 80% chance of successfully fighting off reinfection, indicating that a protective immune response has been induced and that vaccination is a realistic goal. However, with seven distinct genotypes and more than 60 subtypes, the genetic variation makes it challenging to produce a vaccine that would protect against all infections.

HCV is encased in an envelope of glycoproteins that are highly variable and essentially act as decoys, provoking the immune system to produce antibodies that cannot neutralise the virus. We need vaccines that refocus the immune system onto regions of the virus that have essential functions and a stable structure.

A great deal of research has gone into identifying and characterising antibodies that neutralise a range of HCV types - broadly-neutralising antibodies (bNAbs). The region of a bNAb that binds to the HCV virus (in much the same way that jigsaw pieces fit together) is called an epitope. Ideally, we would use those epitopes as a template for designing a vaccine that would cause the immune system to produce the corresponding bNAbs. However, replicating their structure is extremely challenging.

As conventional methods to produce a vaccine have not succeeded, the research team turned to an unconventional approach. It's based on an idea from around 30 years ago, called Jernes' idiotype network theory, which proposes that the immune system generates a cascade of interacting antibodies. One group of these ‘anti-idiotype’ antibodies bind to the variable region of another antibody.

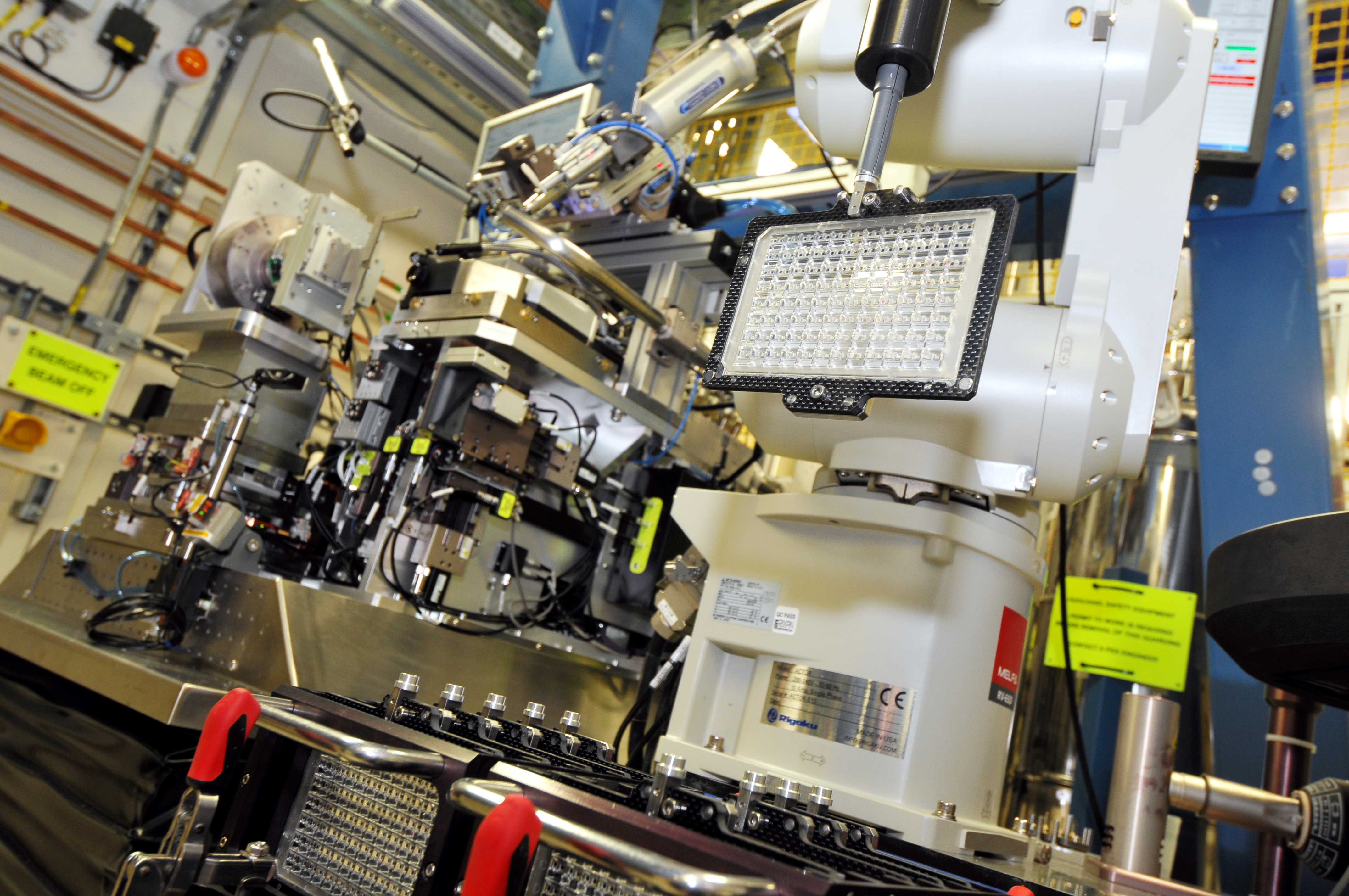

In this case, the team selected a well-characterised bNAb (AP33) to use as a template to reverse-engineer an antigen (B2.1A) that mimics the structure of an epitope but is otherwise structurally unrelated to the viral protein. They used macromolecular crystallography (MX) on beamline I03 to confirm that B2.1 A is a structural mimic of the AP33 epitope.

Initial testing in mice showed that B2.1 A can induce antibodies that recognise the same epitope as AP33 and protect against HCV infection. It is unlikely to create adequate protection on its own, but it is envisioned that this could be used in combination with molecules that target other epitopes. In future, this novel approach may also prove helpful against other highly-variable viruses, including HIV and influenza.

To find out more about the I03 beamline, or discuss potential applications, please contact Dave Hall (Science Group Leader for the MX Group): [email protected]

Cowton VM et al. Development of a structural epitope mimic: an idiotypic approach to HCV vaccine design. npj Vaccines 6, 7 (2021). DOI:10.1038/s41541-020-00269-1. .

Diamond Light Source is the UK's national synchrotron science facility, located at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire.

Copyright © 2022 Diamond Light Source

Diamond Light Source Ltd

Diamond House

Harwell Science & Innovation Campus

Didcot

Oxfordshire

OX11 0DE

Diamond Light Source® and the Diamond logo are registered trademarks of Diamond Light Source Ltd

Registered in England and Wales at Diamond House, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0DE, United Kingdom. Company number: 4375679. VAT number: 287 461 957. Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number: GB287461957003.