First fabricated in 2012, triboelectric nanogenerators (TENGs) are a new power-generation technology that can scavenge mechanical energy from the environment and convert it into electricity. Although they offer considerable promise for powering smart sensors and wearable devices, their current low power output limits commercial development. Recent research suggests that the large surface area and excellent tunability of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) could be exploited to enhance the electrical performance of TENGs. In work recently published in Nano Energy, scientists from the University of Oxford used synchrotron far infrared (THz) probe to reveal how incorporating MOF nanoparticles improves TENG performance. They also demonstrated harvesting energy from oscillatory motions to power commercial microelectronics such as light emitting diodes (LEDs) and a Morse code generator.

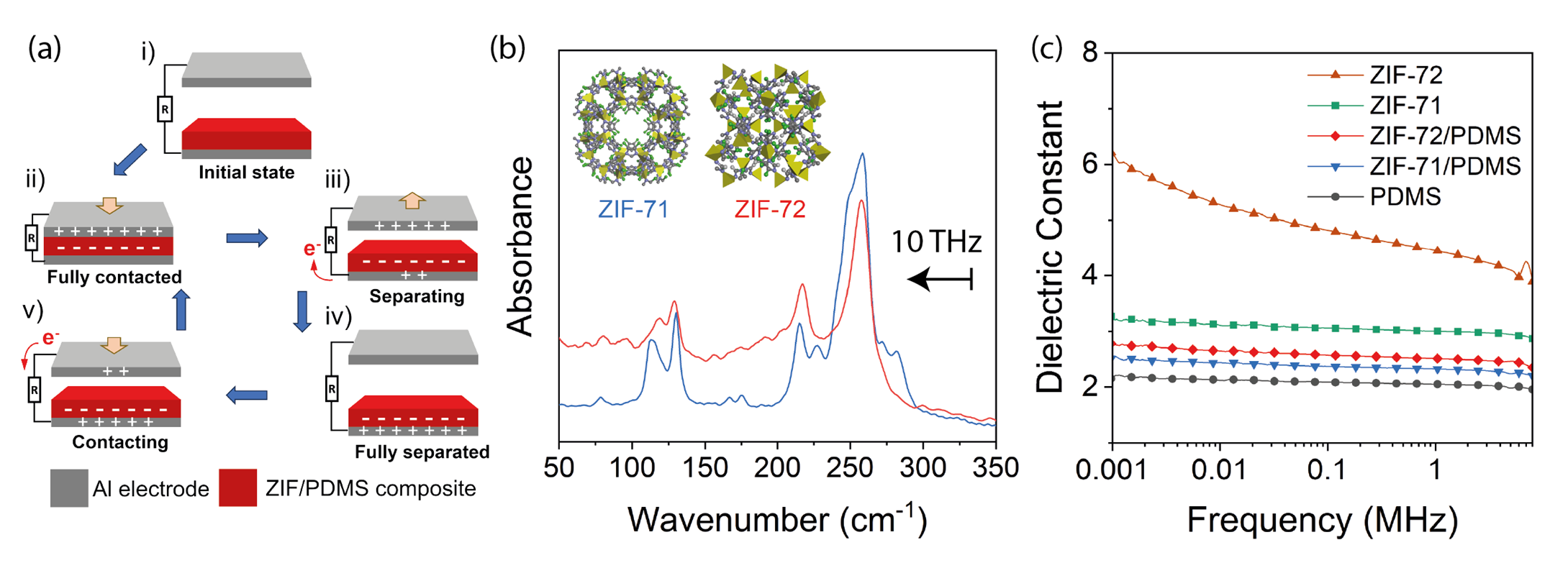

The triboelectric effect involves the transfer of electric charge between two objects contacting or sliding against each other. (Static electricity can result if the charge isn't conducted away and builds up on one of the objects, see Fig.1a) It has the potential to convert mechanical motion - human movement, vibrations, wind and wave energy - into useful electricity. Small-scale devices, such as smart sensors for the Internet of Things (IoT), keyboards and wearable gadgets could be self-powered, without the need for batteries.

Prof Jin-Chong Tan from the University of Oxford explains;

When the community talks about triboelectric nanogenerators, we're not talking about the small size of the devices. We’re building the devices from nanomaterials. MOFs are essentially hybrid materials with metal centres and organic linkages, which self-assemble into 3D crystals. The idea is to harness this kind of crystalline materials to engineer tunable physical and chemical properties for triboelectric energy generation.

TENGs have several advantages beyond their portability and independence:

In this study, DPhil candidate Jiahao Ye synthesised nanoparticles of hydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate framework ZIF-71 and its non-porous counterpart ZIF-72 (Fig.1b), dispersing each MOF into polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS – a mechanically resilient elastomer) to produce thin composite membranes. Lab-scale experiments, including in-house spectroscopy, allowed them to understand the chemical nature of the membranes, and their physical properties.

Professor Tan continues;

We use Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), but there's a limit to how far we can probe with a lab-based technique. The lattice modes at lower energies - Terahertz vibrations - tell us a lot about the structure and mechanisms of the material, but to probe those, we need to use a synchrotron radiation.

Chemically, ZIF-71 and ZIF-72 are the same. However, the research team discovered that the two materials are quite different in terms of their electrical generation output. The very low-energy probes (≤10 THz, see Fig.1b) they carried out at Diamond explain why - they have very different terahertz modes. While ZIF-71 has a relatively open structure with cavities, ZIF-71 is much more densely packed. This molecular-level architecture dictates the nature of the vibrations, and consequently, the dielectric behaviour of the two materials is distinct (Fig.1c).

Prof Tan explains;

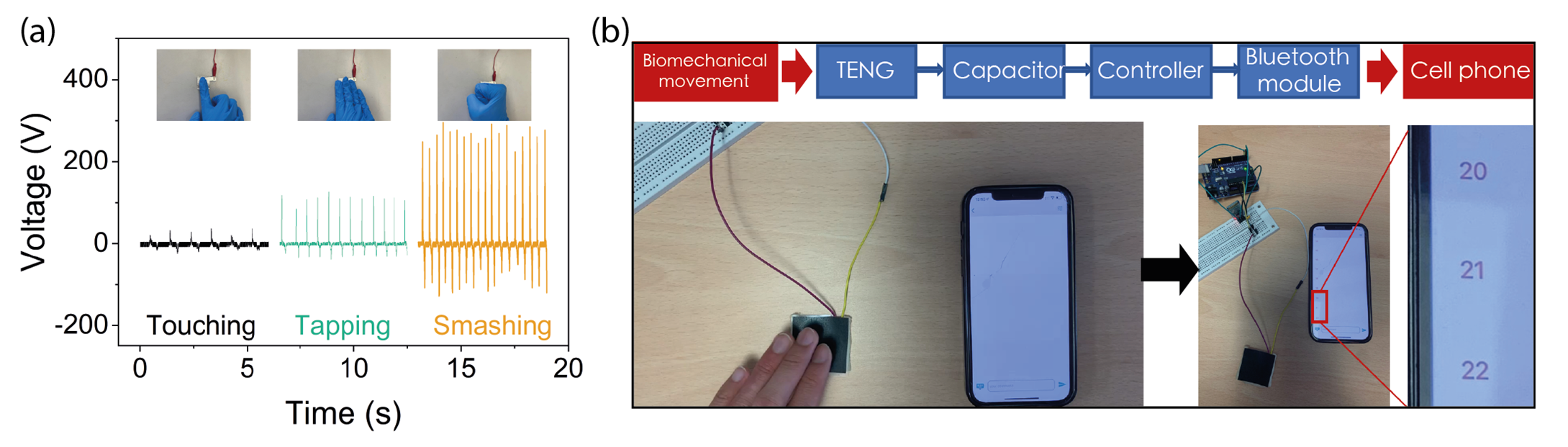

The force needed to generate electricity is not high. The contact separation process is very gentle, and we can harvest that energy quite efficiently. A few Newtons are sufficient to generate the charge, and the charge is reasonably high. We've used our composite membranes to charge capacitors, which are then used to power commercial electronics (Fig.2) - LEDs, timers, calculators, smart keyboards.

Lighting of 300 LEDs using ZIF-72/PDMS TENG in contact separation mode.

The nature of TENGs is that they produce a high voltage and a low current output. Although some capacitors can deal with that, a focus of the ongoing research is developing materials that can deliver a higher current at a lower voltage. Tuning the MOF/polymer combinations offers the potential for improved electrical properties; for commercial applications, durability is also a key factor.

The team is also investigating non-contact modes (sliding systems), which would be perfect for (e.g.) wind and tidal energy harvesting. All of their synchrotron experiments for TENGs so far have been static, so there is the potential for operando studies in the future by leveraging synchrotron nanospectroscopy.

Prof Tan concludes;

We've been working with THz spectroscopy on Diamond's B22 beamline for over a decade to research a vast range of nanoscale materials and bespoke composites; we're very frequent visitors

To find out more about the B22 beamline or discuss IR/THz applications, please contact the Principal Beamline Scientist Dr Gianfelice Cinque: [email protected].

Ye J & Tan JC. High-Performance Triboelectric Nanogenerators Incorporating Chlorinated Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks with Topologically Tunable Dielectric and Surface Adhesion Properties. Nano Energy 114 (2023). DOI:10.1016/j.nanoen.2023.108687.

Diamond Light Source is the UK's national synchrotron science facility, located at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire.

Copyright © 2022 Diamond Light Source

Diamond Light Source Ltd

Diamond House

Harwell Science & Innovation Campus

Didcot

Oxfordshire

OX11 0DE

Diamond Light Source® and the Diamond logo are registered trademarks of Diamond Light Source Ltd

Registered in England and Wales at Diamond House, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0DE, United Kingdom. Company number: 4375679. VAT number: 287 461 957. Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number: GB287461957003.