Keep up to date with the latest research and developments from Diamond. Sign up for news on our scientific output, facility updates and plans for the future.

These articles were published in our popular science magazine: Inside Diamond

Those articles were published in our popular science magazine: Inside Diamond

Latest edition:

This article was recently published in our popular science magazine: Inside Diamond

In 2007 Helen Saibil was at a conference in Australia. Amongst the presentations there happened to be talks on the parasites malaria and toxoplasma and how they infect mammalian cells, causing disease. Helen is a structural biologist and whilst listening she began to realise that her newly acquired skills -she was doing electron tomography of cells- might allow the researchers to see things they had never seen before.

.2020-02-21-14-30-26.jpg)

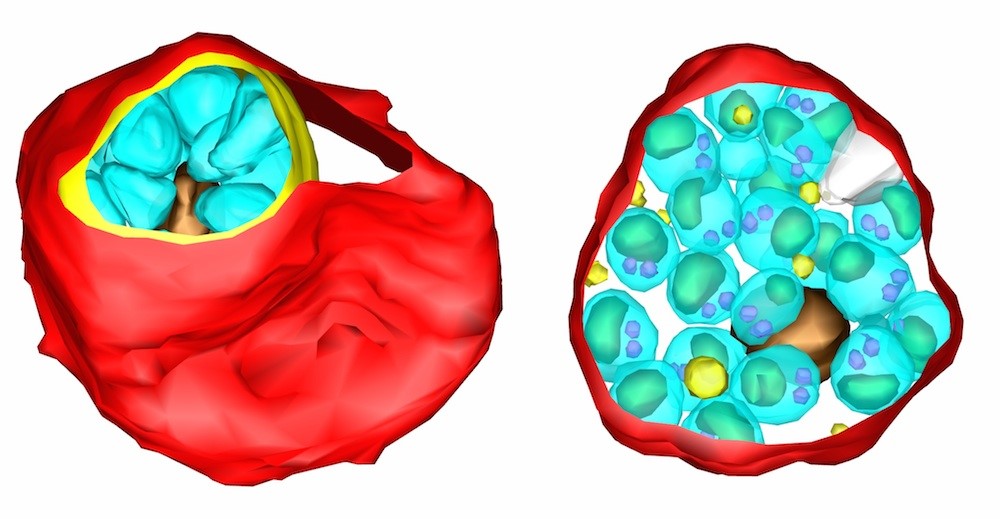

Electron tomography reveals structures in the interiors of cells in great detail. What she hoped was that it could be used to look at the malaria parasites inside red blood cells [See images below] to get a better understanding of what they do there. Helen approached one of the speakers, Mike Blackman, then at the National Institute for Medical Research at Mill Hill in London, and so began a thriving collaboration. One that has produced the remarkable pictures of malaria parasites breaking out of infected human red blood cells on this page.

Helen Saibil and her colleagues used electron tomography to peer into malaria infected cells, looking at the parasites hiding and multiplying inside. The technique produces exquisitely detailed pictures able to reveal very tiny features, but it has one big drawback. Electrons cannot penetrate deep into the sample so it only works on very thinly sliced samples, much thinner than an individual cell. As a result it cannot be used to look at entire cells, or in this case red blood cells containing malaria parasites.

Diamond’s X-rays

One of the many things the Diamond synchrotron can do is to produce a very fine, very intense beam of X-rays that can easily travel through the full depth of a cell and out the other side. This allows the researchers to build up a picture of an entire cell, complete with parasite, in unprecedented detail. Beamline B24 uses a very fine beam of X-rays to see very tiny objects, single cells and smaller. The frozen experimental samples are kept extremely cold and then scanned with the thin beam of X-rays. The sample is slowly rotated in the beam as the detector takes a series of X-ray images. A computer then combines these into a final 3D image. Rather like slicing up a loaf of bread to see inside, without actually needing to take a knife to it. The technique is known as cryo-X-ray tomography, a powerful and often satisfyingly fast technique, producing individual images in less than a minute and a complete cell in an hour or so.

Cryo-X-ray tomography

One key feature of cryo X-ray tomography, cryo meaning extremely cold, is that it is especially good at picking up cell membranes, the thin fatty films that surround the cell and many of its internal components. This is particularly important, it turns out, when studying malaria. The malaria parasite gets into the body via the bite of an infected mosquito. It finds its way into the bloodstream and enters the red blood cells. Once inside it wraps itself up in a bag of membrane which effectively hides it from the body’s immune system. It then starts to multiply. Eventually the new parasites break out of their protective membrane coat and then break the blood cell’s outer membrane passing into the blood and on to infect other red blood cells. This break out, or egress, is an essential part of the parasite’s life cycle.

If it can’t break out the infection cannot spread.

All that was needed now was malaria infected blood cells to study. It is difficult to grow suitable samples in the lab, but Mike Blackman’s team had a great deal of expertise in doing just that, and the Saibil group knew exactly how to prepare thin, frozen samples of the cells. These were put into the beamline and “it worked beautifully from the first try” said Helen Saibil.

For the first time, they could see all the cell membranes in intact, infected cells, during the process by which the parasites break out of the blood cells. This perspective is not obtainable with any other technique. It isn’t a straight line from here to a treatment for the disease, but being able to see the parasite as it emerges from hiding might reveal its vulnerability.

This technique is relatively new but these spectacular malaria pictures have shown its potential. Principal scientist Liz Duke and her team on B24 are constantly working to improve it. Liz says “it is an amazing feeling when you can see something that has never been seen before.” She believes that the method provides a way to see biology in action that could help understand all sorts of important processes. How drugs affect cells, how other parasites and virus enter the cell and how the plastic microbeads now polluting our environment interact with all types of microscopic life. A window into the unknown.

The mosquito is the deadliest animal on Earth, responsible for more human deaths than any other. This is because it carries infectious diseases, the most dangerous of which is malaria. Around one million people a year die from the disease and there are between 300 and 600 million people infected at any one time. Malaria is a particularly difficult disease to tackle, partly because it hides away from the immune system inside red blood cells.

More information about research on Malaria:

Diamond Light Source is the UK's national synchrotron science facility, located at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire.

Copyright © 2022 Diamond Light Source

Diamond Light Source Ltd

Diamond House

Harwell Science & Innovation Campus

Didcot

Oxfordshire

OX11 0DE

Diamond Light Source® and the Diamond logo are registered trademarks of Diamond Light Source Ltd

Registered in England and Wales at Diamond House, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0DE, United Kingdom. Company number: 4375679. VAT number: 287 461 957. Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number: GB287461957003.