Keep up to date with the latest research and developments from Diamond. Sign up for news on our scientific output, facility updates and plans for the future.

The Dzyloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI) was first introduced in 1957 to explain ‘weak ferromagnetism’. It causes a twisting of the pattern of atomic magnets, and is now considered to be the driving force behind the exotic magnetic vortexes called Skyrmions. A predictive theory hadn’t been developed, however, as until now a detailed study of the amplitude and sign of the DMI hadn’t been carried out.

Magnetic order at the atomic scale is ruled by exchange interactions, which are mostly symmetric upon exchange of the spins. In 1957, Dzyaloshinskii introduced an antisymmetric part to explain the weak ferromagnetism observed in a some crystals1. This new term, known as the Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction (DMI), is a key ingredient in many modern magnetic phases, such as multiferroics and skyrmions. Despite the intense research effort on these materials, the DMI still lacks a simple understanding at the microscopic level, in particular because many experimental studies on the DMI address only its magnitude, not its sign. The sign of the magnetic twist is accessible in a handful of long-period magnetic structures, with complex phase diagrams that defy systematic investigations versus band filling.

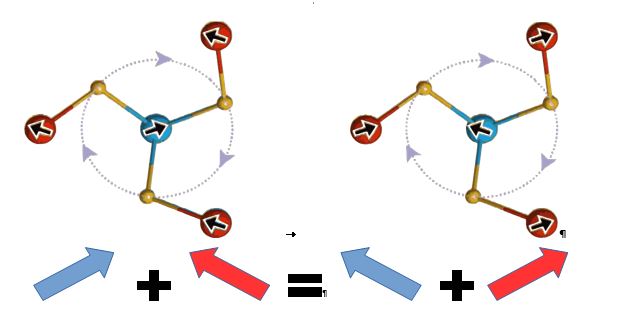

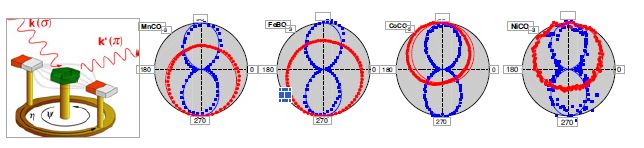

Weak ferromagnets with the carbonate structure offer an opportunity to perform such a systematic study: MnCO3, FeBO3, CoCO3 and NiCO3 share the same crystal structure and the same low temperature magnetic ground state: weak ferromagnetism due to a small canting of the spins away from the collinear antiferromagnetic arrangement (Fig. 1). The main difference is the nature of the transition metal ions, which carry the magnetic moments, and it is expected that the number of valence electrons has a large influence on the DMI. The sign of the DMI in these crystals is directly connected to the direction of the canting of the spins with respect to the antiferromagnetic sequence (Fig. 1), but the determination of this direction is not straightforward. Specifically, the canting direction can easily be driven in any direction of the basal plane by a small magnetic field, which is convenient to ensure a single magnetic domain in the sample, but the phase of the antiferromagnetic structure is needed to extract the sign of the DMI.

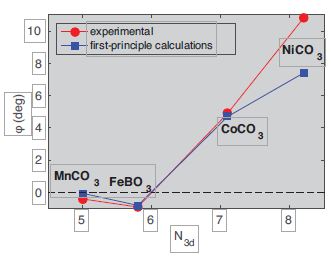

The results3 show a nearly monotonic variation of the canting angle (and the DMI) as a function of the filling of the 3d band, with a change of sign between FeBO3 and CoCO3. This can be understood with a simple model based on partial inter-orbital contributions to the DMI (IO-DMI), following the super-exchange-based approach developed by Moriya4: considering two interacting ions, one considers each of the partial contributions for DMI between one orbital of one ion and one orbital of the other ion. By changing the occupation of the 3d states we change the balance between empty and fully occupied channels for the IO-DMI. It results in the change of sign and magnitude of the total DMI.

This work, relying on a novel diffraction method, provides thus a simple microscopic understanding of the DMI in insulator systems.

Diamond Light Source is the UK's national synchrotron science facility, located at the Harwell Science and Innovation Campus in Oxfordshire.

Copyright © 2022 Diamond Light Source

Diamond Light Source Ltd

Diamond House

Harwell Science & Innovation Campus

Didcot

Oxfordshire

OX11 0DE

Diamond Light Source® and the Diamond logo are registered trademarks of Diamond Light Source Ltd

Registered in England and Wales at Diamond House, Harwell Science and Innovation Campus, Didcot, Oxfordshire, OX11 0DE, United Kingdom. Company number: 4375679. VAT number: 287 461 957. Economic Operators Registration and Identification (EORI) number: GB287461957003.